As most Hollywood fans know, when Disney #cancelled Gina Carano over an innocuous (and true) tweet, The Daily Wire hired her to make movies together. DW had a string of releases already, but Gina is their first in-house talent.

Their first opus is Terror on the Prairie, a gritty, violent, low-budget, mostly contained thriller. DW seems to be making a habit of those: including Run Hide Fight and Shut in, neither of which fully realized their potential.

But like most alt-Hollywood fare, faith market included, supporters hyped them beyond their worth, and declared victory because, “At least it got made.”

I prefer a higher standard. Storytelling is as old as time, and Hollywood has 100+ years of story development experience, so forget remaking the wheel, or deflecting criticism with near non-sequiturs like “Our movie doesn’t have high levels of profanity, violence, sex, socialism or [whatever else].”

What follows is a learning experience, and yes, there will be SPOILERS.

Intro to Terror on the Prairie

Terror on the Prairie (TotP) resembles many recent gritty westerns, directly comparable to Old Henry (2021), with hints of Slow West, The Hateful Eight, and others. If you’re looking for a solid entertainment, pick those.

TotP doesn’t reach its potential for a few basic reasons worth mentioning. Despite its near-identical opening to Old Henry (OH), TotP feels painfully slow, but what you’re experiencing is not necessarily the lack of pace, but of suspense.

Yes, they hired a good cinematographer, but a weak director. Just rewatch that simplistically blocked and badly executed opening chase, or how he fails to build every action scene.

The acting is pretty fair. Nick Searcy carries the film, though his Captain is a shallow character and his scripture spouting got on my nerves early and often.

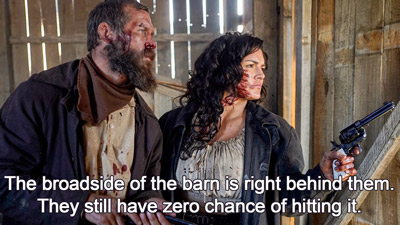

Our star, Gina Carano, does a solid job, does her best with what she’s given, but she hasn’t been effectively directed. That is, she doesn’t communicate without speaking. Her face seems impassive, and she hasn’t found the key light. Yes, blame the director, but she also needs to instinctively convey meaning to the camera through non-verbal means, through the eyes, subtle expressions. (If you don’t know what I mean, watch Harrison Ford or Tom Hanks with the sound off).

Our star, Gina Carano, does a solid job, does her best with what she’s given, but she hasn’t been effectively directed. That is, she doesn’t communicate without speaking. Her face seems impassive, and she hasn’t found the key light. Yes, blame the director, but she also needs to instinctively convey meaning to the camera through non-verbal means, through the eyes, subtle expressions. (If you don’t know what I mean, watch Harrison Ford or Tom Hanks with the sound off).

We get almost no extreme close-ups of Gina’s face, and even in mid-shots, her eyes disappear in shadow. That prevents us from experiencing what she’s feeling until she speaks. That means she’s not carrying the emotion a taciturn character actor needs to.

Yes, her voice a bit monotone, but a few singing lessons should help her find other parts of her range.

All I’m saying is, her first film, Haywire, was in 2011. Gina should invest in a coaching, and if she wants to stay in action flick territory, she should hire whoever works with Helen Mirren.

The Business of Suspense

The story and characters are simply underdeveloped, even for a stripped down thriller. Any character motivation that you can define with one word (“Vengeance!”) is not ready.

But to understand the problem, consider how it failed to develop mystery and suspense. For a primer, consider Hitchcock’s “bomb under the table”: if it explodes without build up, that’s surprise, but no suspense. If you show the audience the bomb, that creates suspense — the anxiety about the bomb going off before the characters sitting at the table realize it.

But then, show the audience that one character knows the bomb’s under the table, and you create suspense and mystery. It’s no longer a question of when the bomb explodes, but who, why, all that stuff that helps sustain the audience’s attention.

Now consider TotP’s first scene: an evil posse scalps a guy and we’re not given ANY reason why. No motivation besides “You know who I am so you know what I’m after.” That’s economy, but it doesn’t give us anything to hold onto.

So when we’re introduced to the McAllister family we have no context. No forward momentum. We spend the next 10 boring minutes watching them before we find out Hattie (Carano) wants to leave this prairie life (first dramatic conflict). But even as the posse arrives, we have no reason to connect them with the family.

That’s not how to keep the audience’s attention (for nearly 20 minutes).

The Old Henry Suspense Opener

To compare, the evil posse in Old Henry’s nearly identical opening scene asks their victim: “Where’d he get to?” That’s economy that establishes mystery (who and what are they after?).

Then we cut to Old Henry and son. We get the family conflict immediately: farming is old school and the kid wants a different life (under 2 minutes!) — plus we know the mother’s dead, Henry’s wise but world-weary, we know everyone’s relationship to each other, their personalities and hot buttons. Two minutes later, a riderless, blood-splashed horse appears on their horizon, drawing old Henry into the fray.

That is a solid opening. It establishes suspense (will the posse reach Henry?), and mystery (who, where and what happened?).

Then Henry finds the wounded thief with a bag of money, creating a moral dilemma: should he help the man or leave him to die while he’s got the man’s horse?

“Nope,” Henry says, refusing the call, momentarily, before he cannily packs up the man and covers his tracks, creating two mysteries: who’s the thief, and who is this old farmer Henry. And possibly: what’s Henry’s plan to keep from getting caught?

Nothing that dynamic happens in Terror on the Prairie.

What Audiences Know About Strangers in a Western

Long before Injuns stole a white girl in The Searchers, before an evil posse massacred a family in Once Upon a Time in the West, audiences knew to be wary of strangers. And no, we’re not “going against type,” William Goldman- Butch Cassidy thing with audience expectations.

When the evil posse arrives at the McAllister’s farm, Hattie begins a series of bad – even laughable – decisions. We already know natives could show up for a gristly scene. We’re already know they’re in debt to the town store for groceries, so when Captain asks to buy food, she should have refused. Or accepted for just enough to send them on their way.

She certainly wouldn’t offer to take them inside the house for a hearty breakfast and let them hold the baby.

Yes, this increases suspense as we wonder when she’s going to realize these guys are killers, but she’s quickly burning up the audience’s good will! And we don’t know if they mean her any harm.

Then when she sees the scalps, she makes a worse choice: ordering them to leave their sidearms and ride off. What did she think they would do: leave? They’re NOT leaving without their guns. Even the good guys in The Magnificent Seven say, “Nobody hands me my guns and says run. Nobody.”

The evil posse doesn’t create this house siege: Hattie does. The Captain is right: it didn’t have to go like this. She had better options. But we’re left with the absurd exchange: “Take what you want and go!”… “But what we want is you!”

We finally get what they’re after when Hattie does, when she shoots the young “reb” in the face. Again, that’s surprise. Had the Captain asked his first victim where Jeb’s farm was, we wouldn’t have wasted all those quiet moments.

You Need Two Sieges

I developed a siege movie for a long time, so I’ve given this a lot of thought. The real problem with TotP’s house siege is that there’s only one.

When the evil posse comes to Old Henry’s door, he stands between them and the door with a gun, half-convinces them nothing’s going on, and sends them away. But he also has their target tied to the bed inside. While the wounded thief’s not healthy enough to travel (a great complication), he’s also not welcome, and he’s a threat to Henry and his son.

That multiplies the suspense and creates more useful plot. Henry doesn’t have time to coo at the baby or teach the son to make coffee or sit and watch the window while the posse plots their revenge.

In ANY story, the writer’s job is to keep the plot ahead of the audience. You can either hide relevant information in the hopes the audience won’t figure it out before it’s time (treating your story like an “Escape Room”), or you can give them enough entertainment – compelling options and characters and situations – that they don’t mind the siege.

Hattie’s choice to cast the posse out of the house imprisoned her, giving her only a few options: draw help toward her, escape, or shoot it out. And that, folks, is the rest of the plot, in that order.

Exceed Audience Expectations

We’re told very few things about the McAllisters. She wants to leave. He’s a patriot sharpshooter and so is their son. So what happened to the epic sharpshooting finale we were implicitly promised?

Once Hattie is captured by the river, we still have options: Jeb could reach his kids first, leave the baby with the natives and mount a rescue mission. Or they could both attempt it separately and come together at the end. Or the Captain could bait either or both of them, play them off against each other for a tragic ending or something.

Instead, by happenstance, Jeb arrives at the river and leap onto them like a pro-wrestler! What was that?!!!

The Captain’s threat, followed by Hattie’s “You can’t trust him!” made everyone’s eyes roll.

Then the couple takes turns surrendering to keep the other from harm, even though we know the posse will kill them both anyway. She even volunteers to be gang-raped to buy time and the bad guys not only agree, but agree to rape her one-at-a-time.

This is how bad writers sustain plot. But by the time we reach the house, the audience already knows Hattie’s going to trick someone, and there’s going to be a shoot out. Our only surprise in the final act was discovering just how bad a shot Jeb really was, based on his reputation.

Meanwhile, Old Henry has more than one stunning revelation to keep us on the edge of our seats until the very end.

Fixing Terror on the Prairie

The Hero's Coping Mechanism

Let’s set aside the idea that TotP is just an allegory of a political left trying to cancel a wife and mother though their hatred of patriotic father figures. The writer said he wanted to tell a tale of the hard life of a frontier woman. Fine.

Start with Hattie’s desire to leave, which was never settled. Sure, they say its Jeb’s passion to own their own stake. It’s really about Jeb’s decision in the war.

They can still tell themselves they’re escaping the temptations of the town to raise their sons as God intended. Whatever. Build the inner world. He betrayed his own civilization. He had to leave. He’s carrying shame, and that makes him determined to seek and eek out a hard life in ways he doesn’t want to admit.

And she doesn’t want to admit that she blames him too. Subtly. She misses the comfortable life. Her friends. She unconsciously wants them to fail, and perhaps she resents her children too, for robbing her of other chances she had in life, because more kids means roots in a hard place.

You see, without a moral coping mechanism — not just a psychological flaw like a phobia — but something that harms others and prevents her from a full life — we don’t have something meaningful for the audience to wrestle with along with the hero.

The terror is facing her false faith in her husband’s patriotic virtue, masking her own resentment.

We might even bring a new perspective to that unnecessary “patch up the squaw” scene. After all, “patriots” put the natives on reservations. Killed them. Hattie staking her future to her husband’s patriotism causes some folks conflict.

Plus, it will inform her decision to be hospitable to a Missouri visitor that doesn’t judge her. Not knowing he’s come to pit her against her own family and destroy her life.

See? We need to get a clear, visceral, dramatic element in place first.

The Antagonist's Plan

The Captain lost a daughter, blames Jeb, so he wants revenge, right? So why didn’t he let his posse kill Hattie at first sight, and just wait in the house until Jeb returned?

Answer: because it doesn’t serve the writer’s story. It’s the best solution for the Captain, especially since he’s going to kill them all anyway! So what is stopping him?

Then consider that burning the farm while Jeb is away brings Hattie closer to her desire of leaving, right?

Do you see how muddled these motivations are? Instead, the Captain’s plan needs be something Hattie can’t live with. Something that will force her to confront and expel her resentments — because story is about revealing character and forcing positive growth or a tragic end.

A simple plot might involve the Captain forcing a choice: “Point out your husband for us and we’ll let you and your children live.” That turns a siege movie into hostage-road movie where she must escape before she reaches her husband.

To set that up emotionally for both characters, reveal that in the war, Jeb tracked the Captain’s wife back home, which resulted in the daughter’s death. Thus, the relationship between man and wife becomes the cause of that tragedy, and of the Captain’s revenge.

Or for more plot, make Captain’s amorphous “revenge,” specific: he wants Jeb to experience the loss of his family the same way he did. That puts the children in the cross-hairs in some ritual, like allowing his evil posse to hunt them down while a helpless Jeb watches.

Wow, that’s dark, right? Yes, and it forces Jeb back into the central conflict. He doesn’t get to sit out most of the movie in town. It might require one of the posse to befriend Jeb, get him liquored up and off guard while the Captain takes control of the farm.

After his “terror on the prairie,” the Captain may even want to kill off his posse to cover his tracks. But before that happy event, Jeb and Hattie are forced to thwart his plan together, if they can sort out their interpersonal conflict first.

Alternatively, with more budget, the Captain could take the children hostage and force a bickering couple into a dangerous exploit that, if they succeed, would allow the Captain to leave rich, after the terror.

Regardless, we’re on our way to a better film because these ideas don’t force protagonist or antagonist into stupid, indefensible decisions. They create more possibilities, and those options equal thrilling entertainment.

Conclusion

Gritty westerns have a long history. Clint Eastwood made a career on them, and I recommend The Outlaw Josie Wales, The Good, Bad, and the Ugly, the under-rated Pale Rider, and his Oscar-winning Unforgiven.

Among the best modern ones is Hell or High Water, with Chris Pine and Jeff Bridges.

And to the DailyWire, while I understand the impulse for a growing organization to push out a few cheap thrillers to prime the creative pumps, I would recommend spending more time developing a stand-out property like a The Sixth Sense, Driving Miss Daisy or Passion of the Christ before releasing another derivative Terror on the Prairie.

Better yet, develop a TV show to syndicate. The conservative crowd has long wished for a more balanced (or less preachy) West Wing, but based on our current social conflicts, I think a conservative Welcome Back, Kotter is a more promising idea. Very few sets, local talent joking about whatever needs mocking. You might even get social media to help you develop episodes.

Regardless, I wish you well. Just, get the story right before you green-light. We don’t need a derivative Hollywood, but better plots to the future.