Those who do not learn history are doomed to replace it.

We’re currently awash in current event stories (e.g. Patriot’s Day) competing with historical revisions (Man in the High Castle), alongside documentaries (Hillary’s America), fiction with stupid-simple history horribly wrong (Assassin’s Creed) and even historical revisionism masquerading as documentaries (whatever Michael Moore is up to).

What audiences want is both “the sweet and the useful,” the entertainment and enlightenment, and for that to work effectively, I believe storytellers need to keep history intact.

This is the great challenge. Since Cain we’ve had revisionism and since Aristotle people have tried to compress their tales into one time and dramatic movement. One of our most famous stories, Shakespeare’s Macbeth, bears little resemblance to reality (if anyone cares). Macbeth displaced a horrible Duncan, ruled honorably for 19 years and was indeed killed by a snot-nosed prince who used foreign armies to win. Perhaps the Scots are sticklers but Burnham Wood didn’t come to Dunsinane and Macduff was not untimely ripped and all that.

Nevertheless, it made for great art.

Nevertheless, it made for great art.

I can’t say the same for Assassin’s Creed (2016), which used practically the same cast as Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth (2015), and which claimed that a secret order of Assassins (as in Man of the Mountain Muslim cult of Assassins) prevented the Templars, which apparently controlled Spain in 1492, from possessing the Apple of Eden in an attempt to control humanity’s free will to stop violence.

Huh?

I trust the video game is better, but anyone doing even the scantest research would discover that the Templar religious order was suppressed by the Pope in 1314 (178 years earlier) and that the cult of Assassins (hashish-smoking psychos) were eradicated even earlier.

My fictional tale, Knight of the Temple, is far closer to reality, and I believe exemplifies what we should strive for in developing slightly altered versions of history.

First, do no harm

When developing a narrative, much like an archeologist uncovering fossils, try to keep the artifact intact. To be useful, your history should be as accurate as possible, so that your fiction will embellish, or reveal what is unknown. That is, research enough that you know the parameters of your story. For some writers, that is the joy.

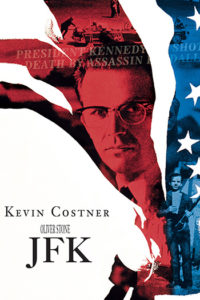

Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991) took great pains to recreate the actual footage of the Dallas assassination, and populated the drama with so many life-like characters that it looked real.

For my Wittenberg, a Prequel to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, I combined the fictional character’s backstory with Martin Luther’s history along with elements of the conflict between Sweden and Denmark into a whole that didn’t detract from any of the sources.

Find the story/history’s essence

What is the essential truth of that moment? As writers, we don’t choose a period piece for the decorations. Yes, we may want to harken back to a time without cell phones or when zoot suits were in fashion, but really, we want to seize the zeitgeist, the spirit of the age — the essential truth that reveals our humanity.

As a leftist, Stone wanted succeeding generations to share in his country’s loss to Camelot, to eulogize JFK on film.

I’m guessing someone wanted to express the peace and music-loving, passionate side of the German people when they developed Swing Kids (1993), which captured the daring rebellious youth who danced during the rise of the Nazis.

Ask “What if”

“What if” is the genesis of creativity and it’s no different here. What if Macbeth was racked with guilt over killing Duncan? What if Richard III was a manipulative monster (I mean, who’s going to form a society to restore the good name of some hunchback king)? What if the allies lost WWII? What if there was no magic bullet but someone else shot from the grassy knoll?

Early in my research, I asked — what if the Last Grand Master of the Templars told the truth?

Let the Weeds Grow

Follow your “What if” with, “What are the ramifications? What changes? How does the story open up if that’s true?” See where the creativity takes you, and see if the history provides confirming evidence. Read up on ancillary things.

Let the weeds grow in whatever direction it will. Don’t rush to the page just because you know structure and the protagonist can only do X so X is how it happened.

I took a full year to research and discarded various potential paths before settling in and discarding interesting but not persuasive paths for my story. Not only did I read up on the trial of the Templars, but on European life in 1300, medieval ships, the occult, other literature of the period, etc.

If you’re claiming a faithful recreation of a moment (9/11, Boston Bombing, etc), everything better be accurate. Don’t let your politics blind you, especially for current events. Those who know are unforgiving and will call bulls–t on you. I’m looking at you Fair Game.

Or what if 9/11 was an inside job, that GWB detonated the Twin Towers for the tax write-off? Well, besides pissing off everyone, do you know what’s involved in performing a controlled demolition of a high-rise? Could a reportedly stupid POTUS execute such a large operation right under the noses of thousands of suspicious NYers with split-second timing while they’re recording and posting planes flying into the building on national TV! Geez, give it up already — It didn’t happen!

Okay, where was I?

Choose the break point carefully

It’s easy to see why we need diverge from reality. Some stories that are harder to tell, that don’t fit what audiences expect from the form. Epics become episodic without a very strong narrative spine and drive. Sometimes the dates don’t line up, and the hero you researched turns out to be a jerk.

Stone went off the rails by claiming that a known, committed communist who spent time in the USSR and who hated Kennedy for opposing the spread of communism in Vietnam, was actually a patsy for a grand conspiracy that included the Republicans, the mafia and LBJ himself. That was the movie’s problem. Stone couldn’t accept the reality of a villain too close to his own beliefs.

Stone went off the rails by claiming that a known, committed communist who spent time in the USSR and who hated Kennedy for opposing the spread of communism in Vietnam, was actually a patsy for a grand conspiracy that included the Republicans, the mafia and LBJ himself. That was the movie’s problem. Stone couldn’t accept the reality of a villain too close to his own beliefs.

So where do you break? I believe you choose the era for its VALUES first. Values make up your theme, and theme is your story (see Unified Structure).

Swing Kids involves the individuality of dance kids and the conformity of Hitler youth. Macbeth involves ambition vs. guilt. Knight of the Temple involves church vs. state, truth vs. propaganda, the need to know vs the need for secrets, etc.

Choose the genre that expresses the values with the right emotion

Before genre we had stories and the audiences interested in feeling certain emotions. These eventually became codified to all those rows on Netflix, but genre is based on the emotion elicited from the audience.

Stone wanted to logically and dolefully rejudicate the JFK assassination so leftists weren’t at fault. So he picked a crime drama with a ton of flashbacks.

Swing Kids failed at the box office because they couldn’t break out drama. It might have succeeded with more comedy the way Life is Beautiful did.

Assassin’s Creed as video game action film failed not just because they failed at basic history, but the human level, which comes next.

I realized early in my research that the reason the Templar story was never told was that it involved years of boring church councils involving heresy and canonical law. So instead of letting it die a legal drama, I summoned my inner Errol Flynn and wrote it as a swashbuckling mystery adventure.

Choose your Gump

Choose your Gump

That is, a single character we call the protagonist must deliver that emotion and theme through a human experience. Forrest Gump is a movie of many things, and to make it all work, we needed to see the tumultuous 1960s through the eyes of Forrest.

Your historical revisionist story needs a Gump too. Ask:

- Who benefits or loses the most?

- Whose seat gives the audience the best view of the arena?

- Who learns the greatest lesson, crosses the greatest distance?

- Who is forced to change the most (character arc)?

THAT should be your protagonist.

For JFK, Stone chose a prosecutor obsessed with the events in Dallas. He didn’t choose Lee Harvey Oswald or Jackie O because that would have limited his story possibilities.

For Knight of the Temple, I couldn’t stick with the guys stuck in prison. I already knew Molay was going to the stake (spoilers), so I needed Elias de Catalan, the knight left in the cold, to carry the theme.

And with a Gump character carrying the theme and the writer’s vision, no one can accusing you of trampling on graves or their memory.

For Wittenberg, I needed Hamlet to be whole and prepared for his monumental sequel, so it was easier for me to make him the antagonist, because antagonists typically don’t change. While my Hamlet did arc, I gave the larger character change to Galen, my protagonist.

Speaking of antagonists, while Cinderella Man (2005) is mostly accurate for James Braddock, Max Baer was the controversy. Max did indeed kill a guy in the ring, but the experience all but finished him professionally. He lost his next four fights, and ultimately turned to character acting. So despite that, and the reality of Max was a hero to the Jewish community, Ron Howard needed a palpable threat for his protagonist, so Max became a remorseless killer. That decision raised some eyebrows and may have limited the movie’s appeal.

Speaking of antagonists, while Cinderella Man (2005) is mostly accurate for James Braddock, Max Baer was the controversy. Max did indeed kill a guy in the ring, but the experience all but finished him professionally. He lost his next four fights, and ultimately turned to character acting. So despite that, and the reality of Max was a hero to the Jewish community, Ron Howard needed a palpable threat for his protagonist, so Max became a remorseless killer. That decision raised some eyebrows and may have limited the movie’s appeal.

But what the story did right was Braddock’s humanity. You felt the struggle of keeping a family together in the depression.

Forrest loved Jenny and his struggle to maintain his innocence in the experience of Vietnam and after made the story more rich.

Choosing your Gump is not merely a way of stringing story beats but fusing real human frailty and emotion to the values in your theme.

Then choose what to compress

History just doesn’t cooperate with our Hollywood expectations, darn it. So, when faced with a problem, compress. Compress dates, and conflate events that make the same dramatic point. Compress that great mass of humanity into specific characters that carry the theme’s values, the plot, and the audience’s perspective. Keep the essential reality intact, but make the history work.

Notice that I put compression at the bottom of the list. Tell the truth first, then embellish.

Gettysburg (1993), is a magnificent example, full of rich characters and accurate to the history. They probably compressed some time elements, and certainly compressed characters, but no one feels duped. They conveyed the realities of that conflict beautifully.

For Knight of the Temple, the story was humming until I discovered that my main antagonist died a year before the final speech! Instead of compressing, I performed an “elision”; that is, I didn’t move the date but I didn’t announce the date either. By emphasis, de-emphasis, and then loud emphasis, I was able to move this impactful story beat closer to the end without anyone noticing. Then I promoted the second antagonist who stood to lose based on that death into first position. Thus the forces of antagonism don’t diminish and I maintained the primary conflict.

For a bad example, Braveheart (1995) didn’t follow any of the above. The theme was likely pulled from the air, genre was chosen and heroes and villains emphasized almost independent of the history. The movie works as art, but it could also be easily transported to ancient China or an alternate universe without anyone griping. The history didn’t stand in the way of a good story.

Movies like that — sweet but not useful — should come with a warning label: JFK, The Patriot, Pearl Harbor, Spinal Tap (cough), etc.

Other works soar as history — useful but not sweet — tend to become docu-dramas, and win TV miniseries awards, and we tend to forget those quickly.

To be great, writers need to their stories to be the full package. What are your best examples? Lincoln? Lawrence of Arabia? Does Bridge of the River Kwai count? My history of around that is fuzzy. Elizabeth? Like did people really catwalk through the castle with wind sweeping by their capes? And what was up with that torture-porn Passion of the Christ? I don’t care if what anyone says; Errol Flynn in Adventures of Robin Hood was just the way it happened…