We all love Mission Impossible movies — action thrillers about a single man or team forced into an absurd struggle against overwhelming odds.

But this time it’s World War II. History is in the balance! And all we have to save the day are classic, flawed heroes.

Why? Because I recently met a writer developing just such a story and she had NO clue about any of the foundational films of this subgenre.

So, the following is for those who love the Mission Impossible series, and/or for writers contemplating a serious war thriller. They are templates to know, study, discuss, and in some cases, emulate.

Unlike most modern action thrillers, these movies have a clear external opponent. That is, somewhere along the line, Hollywood caught the idea that external opponents (AKA foreign bad guys) are not as interesting as intimate opponents (disillusioned, home-grown, former-good guys).

Suddenly,

- Mission Impossible’s villain is not a cold war conspirator or terrorist, but Phelps – the leader of IM team!

- Jason Bourne is fighting evil American bureaucrats instead of Carlos the Jackal!

- James Bond is fighting rogue double-O agents instead of SPECTRE and Communists! And Blofeld is now Bond’s brother or something?

- American Assassin is fighting a former ops guy getting revenge instead of foreign terrorists, and Iranians.

Our promise: Mission Impossible: WWII edition is about fighting actual evil Nazis.

The Guns of Navarone

The Nazis surround two thousand allied troops in the Greek isle of Kheros, and plan to eradicate them in a final assault in six days. British HQ sent an air assault and they got decimated, so the allies plan to sail into the Aegean Sea to save them. In their way are two enormous cannons mounted into the cliffs of Navarone.

These radar-controlled guns could sink the whole fleet when they come within a mile of the island. The two thousand soldiers are doomed…

Enter Mallory (Gregory Peck), the “human fly” rock climber, who is tasked with taking a small band of men up the 400ft south face of Navarone in a desperate attempt to take out the guns.

As expected, everything goes wrong. Franklin (Anthony Quayle), the team leader, breaks his leg, and Mallory must take command, find the inland partisans, avoid capture, and get Franklin to a doctor before he dies.

My FANs (that’s Film Appreciation Night at Epiphany Space in Hollywood) first noted how propagandistic, even jingoistic, the movie was: “It’s the kind of film that makes boys want to become killers for their country.”

My response: “They’re fighting NAZIS! If there’s EVER a good side, it’s this one.”

After that awkward silence they found the daring twist! (SPOILER) The traitor is a WOMAN! Finally, sexual equality in an action movie, I guess.

Plus, the allied soldier who should have executed her doesn’t. Mallory does.

Screenwriting Notes

The protagonist gets to turn the story. It’s Mallory’s job to kill traitors that turn the story. Don’t give away major plot points to anyone else. And then, make it a character-defining moment.

Some noticed that if Hollywood rebooted it today, it would have a faster pace. After five days of being chased and abused, our heroes weren’t sprinting at the climax — they stroll!

But as the discussion developed, two important notes came out:

ONE: Guns of Navarone is a true action thriller template. Each story beat clearly and effectively breaks down the required action, and can be used not only for other action thrillers, but for not non-military tales, like heist movies (Oceans Eleven) and even teen comedies (Superbad).

TWO: Guns of Navarone uses interpersonal conflict among the team members to make each scene crackle:

- Franklin is Mallory’s friend, but in each scene Mallory has to decide whether to abandon him to the Nazis, risk capture getting him to a doctor, or kill him

- Brown, the knife-wielding mechanic who hesitates under fire, needs to prove his worth to Mallory

- Miller, our explosive expert, hates authority, and resents Mallory taking command

- Spyros wants to kill Germans more than succeed in the mission, but our partisan contact turns out to be his sister

- Anna, the mute former school teacher, desperately wants Mallory to give up the mission before it’s too late

- Worst of all, Andrea (Anthony Quinn) holds Mallory responsible for the death of his family, and promises to kill him at the end of the war (or possibly at any other convenient time)

Just as the Nazis provide unrelenting external conflict, the interpersonal conflict within the team drives each scene, forcing characters to wrestle with their personal demons and somehow “get the job done.”

Altogether, the movie’s great structure and interpersonal conflicts garnered The Guns of Navarone seven Oscar nominations (won for special effects).

And it’s my template for team-driven action thrillers. Get to know it.

Morituri

Marlon Brando in Morituri is a great comparison piece to Guns of Navarone because it follows a few unfamiliar paths that resulted in a box office disaster only a few years later in 1965.

The story is about Crain (among other names), a pacifist German engineer who deserts the Nazi cause, hiding out in India until he’s grabbed by the British and blackmailed into a suicide mission.

Seventy thousand tons of raw African rubber is leaving from Japan toward Europe, and the Allies desperately need rubber to keep their war machine going. They intend to intercept the ship along the way.

But there’s a hitch: the ship has an unknown number of scuttle charges (explosives) designed to sink the ship if it falls into enemy hands.

Crain is sent aboard impersonating an SS officer to find and disarm the explosives before the rendezvous.

If he fails, he’ll go down with the ship. If the ship reaches Europe, he’ll be shot as a deserter. So his survival is a very small window of luck.

The Captain (Yul Brenner) thinks Crain is aboard to rat him out as a drunk, and the anti-war activist criminals working in the engine room plan to kill this SS officer and escape.

If those conflicts weren’t enough, unbeknownst to anyone aboard ship, a Nazi submarine follows them. Complications ensue.

I love the story’s mounting tensions but several things made the story difficult:

The Unsympathetic Protagonist

Brando first played the role of a likeable Nazi in The Young Lions, but in this outing, Crain’s personality and beliefs don’t make you root for him.

He comes off like a lazy playboy, bullied into the mission. Plus, we don’t know what skill set he has or will need to succeed. In Navarone, Mallory’s the climber. Miller’s the explosive guy, etc.

Crain’s character is not effectively developed so we don’t know what to expect. He’s resourceful and cool under pressure (especially in his interrogation scene) but since we don’t know him well enough, we attribute the character’s cleverness to the writer (taking us out of the story).

The “Why Should We Care?” Mission

Kyle believes is that since war is stupid and useless so this mission is also meaningless. That is, unlike the 2,000+ men about to die if the Navarone team doesn’t succeed, Kyle (and the writers) can’t quite articulate why we the audience should care about stealing rubber for the war machine.

The result: my FAN group didn’t really sign onto the mission. I had to explain how important and significant the supply of rubber was to the war effort afterward (see Chaim Weizmann)

Confused Conflicts

This isn’t a point about the number of potential conflicts or its escalation; Morituri has the multi-point opposition in spades. That is the genius of the movie.

No, it’s that:

- The Captain isn’t a primary opponent, and doesn’t really care about the ship. His grief over his patriotic son getting decorated for sinking a hospital ship doesn’t impact Crain.

- The Nazi second in command isn’t a true main antagonist because he lacks power

- The Nazis on the sub don’t offer sustained conflict so there’s no worthy villain

- The activists’ goal is to escape to Hong Kong, or some random island, which not only doesn’t hurt Crain, he would want to go along!

- The “Jewess” Esther brings great tension, but an alternate theme!

The result is that Morituri’s characters and subplots don’t converge on the single point of the mission, and that muddies already murky waters.

The Ambiguous Ending

Say what you want about Navarone‘s big explosions, tied-up character journeys and trite “I didn’t think we could do it either” ending lines. At least the audience was satisfied.

Morituri ends (SPOILER) with the ship adrift, with only the Captain and Crain waiting for Allies to show up. We don’t know if they ever arrive, or if the men die, if the rubber is of use, etc.

Thus, the story violates the “Essential Question” rule of screenwriting: that is, the audience establishes a meaningful question early in a movie that must be answered if they’re to be satisfied. For any war mission movie, the question is: does the hero complete the mission (putting the world right)?

The answer in Morituri is simply not answered, and that is ultimately the reason why most people have never heard of it, despite its great cast.

It’s worth studying, more for its flaws than for its benefits. While the set up is conceptually brilliant, the filmmakers didn’t quite execute on character development, and rising tensions that are connected to the single mission and theme (unless you accept that all war is both stupid and unfocused).

A Man Escaped

Robert Bresson’s 1956 realist film, also known as “A Man Condemned to Death, Escaped” daringly puts its spoiler in the title. And it’s a true story “Told without embellishment”..

Fontaine is a lieutenant in the French underground movement, who gets captured and begins the film by trying to escape from a car. Nazi soldiers beat him and stick him back in. He quickly finds himself in a tight prison awaiting sentence and execution.

Because he knows that his fate is obvious but not immediate, he hatches a plan of escape. He pretends to be injured to prevent his interrogation. He goes to work on his wooden cell door with a spoon while trying to recruit other prisoners, many of whom are resigned to their impending death.

One “partner” is executed before they can finalize plans. Once Fontaine is sentenced to death, he’s given a roommate, Jost, forcing Fontaine to make the choice: do I assume Jost is a spy and kill him and escape, or do I convince him to go along?

What makes Bresson’s work compelling is not the character development and acting. In fact, Bresson believed that decent actors doing their craft “detracts” from the story. So he used ordinary people that do a terrible job at acting (almost on purpose!).

I personally think that Bresson is totally wrong. Bad acting detracts from the story, which is why even his best work is almost unwatchable. (sorry)

What makes A Man Escaped compelling are the details. We don’t race from set piece to set piece to Oscar bait speechifying to CGI thing. No, we sit in the quiet present… Listening… Scraping… Sneaking… Anticipating…

The work belongs on a Mission Impossible list because it reminds writers of the importance of the “business of the scene.” Instead of focusing on intricate plotting, Bresson focuses on the minute, the tension of staying in a terrified protagonist’s present time, experiencing an oppressive silence, a faceless enemy, and a ticking clock without knowing how much time is left.

Bresson also infuses some expression of Christian beliefs, the theme of [heroically] pursuing your salvation through faith, rather than passively waiting for miracles or death.

However, Bresson’s alternative title is “The wind bloweth where it listeth.” The full verse is:

“The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.” (John 3:8)

So, is the movie actually saying that Fontaine is saved by God because of or in spite of his efforts? Or that Jost achieves salvation by Fontaine’s efforts? The movie doesn’t make that clear.

To reiterate for thriller writers, A Man Escaped reminds us to build suspense organically by establishing a tension inducing situation, and then by focusing our attention on the details. It doesn’t have to produce a CGI explosion-fest to be compelling. Real and personal also works.

Notorious

Hitchcock’s 1946 “perfect film” stars Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in a love story/spy film (or possibly spy film/love story) about bringing down Nazis hiding out in Rio.

Party girl Alicia (Ingrid), daughter of an infamous traitor for the Nazis, meets US spy Devlin (Grant) in one of her drinking binges. He offers her a way out: a spy job in Rio to restore her name.

On the way, Alicia learns that her father killed himself in prison. Instead of mourning, she feels that she no longer has to hate him or herself.

She and Dev fall in love while waiting for the assignment. She imagines the joy of sober, married life with Dev, while he struggles to trust her for her past.

Then the assignment comes: she must woo a former flame, Alex Sebastian (Claude Rains), working with Nazi scientists. She must learn what she can and report back to Dev.

She wants Dev to stand up for her. Dev wants her to refuse, but neither are emotionally mature enough to choose love over duty (THEME!), so she takes the assignment.

Alex immediately notices that Dev loves Alicia so he presses her into marriage. Again, Alicia silently implores Dev to man up but he refuses.

She marries, and throws a party, in which she and Dev realize they’re developing a Uranium ore, stored in wine bottles.

But Alex realizes that he’s married a US agent, and slowly poisons her.

It’s up to Dev to choose Alicia over the mission in order to save her and bring the conspirators to justice.

I admire the tightness of the script, the use of subtext, and the symbols of Dev’s scarf, the liquor bottles and the Unica key, but it’s not exactly a perfect film.

The big problem involves the Nazi clique. They KNOW Dev and his boss are agents but do absolutely nothing about it. Dev strolls around suspiciously, making Alex jealous, but no one waits to knife him in a doorway or thwarts his rendezvous with Alicia.

Plus, while these Nazis establish their dangerous credibility by killing Amil, which sets our dread for Alicia and Dev and foreshadows the ending, but that same killing doesn’t raise any flags in Rio?

Then the US government bugs Alicia’s Miami apartment for 3 months and makes records of all those conversations, but they can’t bug Alex’s house in Rio while he and Alicia are on their honeymoon? Or before she enters his life?

Then there’s the love story: Dev is unlikable because we don’t get a backstory to explain why he’s silent over Alicia. Yes, it’s unprofessional to fall for her, but it seems insufficient.

The “pain” he admits at the end makes him seem childish. After all, wouldn’t the job be easier for Alicia had she known Dev loved her? Doesn’t alienating her emotionally make her want to side with her husband, which is a lot worse than getting perpetually drunk? (NOTE: both Atomic Blonde and Red Sparrow play with this possibility)

Now, consider the love triangle if Claude and Cary switched roles. That is, what if Alex were the hot guy with the money and confidence, instead of the older, shorter, mama’s boy? Then Dev would actually fear his competition, become jealous, make mistakes, increase his personal danger, and possibly make Notorious more dynamic.

Yes, those changes would make it less tight. However, it would also make it a more modern spy film. We’re used to more plot, jeopardy, and more love, in our “Spy Who Loved Me” films.

For writers, Notorious provides an additional challenge: love stories are about two protagonists learning to love, but thrillers (spy films included) are about single protagonists or teams making active choices that turn the plot. This narrative follows Alicia primarily, but she’s not the prime mover. Dev recruits her, demands the party, and owns the third act by proclaiming his love in order to rescue her.

That’s an intricate balance, between having a passive (Alicia) protagonist (where the plot happens TO her rather than BY her), and a story where we’re not following the protagonist (Dev). The love story (dual protagonist) resolves this, but it’s very easy to lose balance with this mixed genre.

Fortunately, Tom Cruise remade Notorious, making the Dev character drive every moment of the story. Unfortunately, with John Woo directing, it became the least liked: Mission Impossible II. (and now you know the rest of the story, 🙂

Where Eagles Dare

Along with Guns of Navarone, this Alistair MacLean classic also sports a diverse set of troops daring certain death to complete their secret mission.

Here, an American general is captive in the “Castle of the Eagles” behind enemy lines, and he knows the plans for Overlord. Seven paratroopers, lead by British Major Smith (Richard Burton) and US Ranger Schaffer (Clint Eastwood), must rescue him before he talks.

They paratroop into a snowy forest, losing the radio operator on the landing. His neck break looks suspicious. Or at least Smith considers it suspicious.

Another “red-shirt” dies outside the bar in town, but we don’t know the full score until Smith reaches the German officers holding the American General, and holds a gun over Schaffer and the others.

That’s when Smith reveals that the General is actually a corporal used as bait for the last three red-shirts, who are actually Nazi spies. He pretends to be a Nazi spy himself, and orders them write down their associates to avoid a Nazi interrogation.

He then collects their lists, and reveals his true mission: to uncover the Nazi spy ring.

They shoot their way out of the castle, escape through the cable cars, shoot their way through the airport and escape into the air.

Look, I enjoyed the spectacle, and despite landing on so many war thriller best-of lists, Where Eagles Dare is the weakest story in the nest.

The main problem is, it fails to develop character. Smith is too secretive, and the plot too convoluted to follow until the “interrogation” scene.

Because we never discover the hopes and fears of Smith and Schaffer, we don’t fully sign onto their mission. And once we discovered the mission, we all wondered if they had to go to all that trouble. Couldn’t they have leapt into an allied country, disguised a whole acting troop as Nazis and duped the spies without fighting their way out of enemy territory?

Incidentally, the movie 36 Hours came out 4 years earlier, and was exactly that: the Germans capture an Allied officer and convince him that he had been in a coma for several years, and so, ask him the details of the Normandy invasion supposedly now in the history books.

But Where Eagles Dare wasn’t so clever.

EDIT: Had I known it at the time, I would have concluded my MI-WW2 series with a different movie, one that didn’t lose itself in spectacle:

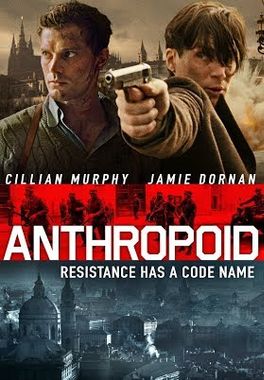

Anthropoid (2016)

It made only $5M at the box office. No one talks about it. It’s almost a miracle I found it. But it’s worth seeing, especially for screenwriters in this subgenre.

Two allied spies paratroop into Czechoslovakia and discover that their mission is to assassinate Reinhard Heydrich, the main architect of the Final Solution, third in command behind Hitler and Himmler, and the leader of Nazi forces in Czechoslovakia.

With little support, they marshal some local partisans, plot and attempt the assassination, and then die in an epic gunfight in a church.

True story.

What makes this tale impressive is how banal the actual planning and waiting is. Each missed moment, dull conversation, and awkward pause FEELS real. This isn’t a Hollywood spy movie, it’s real (scared) people daring something they’re barely trained for.

Even the partisans try to countermand their orders because they don’t want to die (and sacrifice other Czech lives) on England’s whims. It’s that real.

What doesn’t work is the romantic subplot. It starts innocently enough: the leader, Josef (Cillian Murphy) asks a couple of women to meet with them in the bar so they blend in.

The women show up and they’re so hot and put together that it has the opposite effect: the Nazi soldiers are drooling over themselves and staring. Josef actually reprimands them for looking too good!

Sounds great, right? Clever reversal.

But then the gals become “insta-brides” (she may have her own opinions, work a different job or whatever, but her role in the story is to love the hero deeply and unconditionally).

In other words, we don’t buy it. And there’s hardly a moment with the guys and gals that doesn’t fall flat and feel forced.

Perhaps they were added in development to try to pull in a female demographic? I don’t know, but it was the wrong decision.

Better to make her the traitor like Guns of Navarone did!

In the end, when Josef is having his “Butch and Sundance” moment in the church basement, he sees and walks toward the angel of his gal… and it fails to produce the emotional satisfaction we want.

It’s no Braveheart seeing his wife in the crowd. It’s just another screenwriter trying to turn an underdeveloped relationship into a tearjerker.

Unfortunately, the movie didn’t need that. These true heroes are exactly that, and they died on their feet. That’s the best we could have hoped for.

Another version of this story worth viewing is Operation Daybreak (1975).

Conclusion

Had I more time I would have included Billy Wilder’s outstanding Five Graves to Cairo about a soldier who stumbles into spy mission of opportunity, and possibly Donald Sutherland as a German spy in Eye of the Needle along with a few others, but the above will set you up on that impossible WWII mission.