Don’t be afraid of subtitles. Be brave, and explore the absurd creativity of French director, Jean-Pierre Jeunet. He is the proud creator of several bizarre, whimsical, romantic, and fun films, some of whom are on film lovers’ favorites list.

Jeunet’s stories are full of unique characters and vivid detail (Alien Resurrection notwithstanding).

Much like Hayao Miyazaki’s gloriously overstuffed anime, this list should be both inspiration and warning to all daring to fill out their tales with bizarre detail.

Delicatessen

Jeunet’s first feature is a [okay, I’m going to stop saying bizarre] engaging black comedy of post-apocalyptic France, where several people live in a tenement above a butcher shop.

The butcher takes dried corn for payment, and he serves up… Well, people.

His last assistant tried to escape (and he was delicious), and his new assistant is Louison, an ex-clown with a rare ability to stay alive. And the butcher’s daughter Julie falls in love with him.

Each floor conspires to serve up Louison in the hallway after midnight, while Julie invites him for tea (which puts him to sleep). They play beautiful music together, she on the base, and he on a saw.

Meanwhile, troglodytes (yes, vegetarians who live in the pipe system below ground) conspire to steal the butcher’s corn stash.

FANs loved the story, and noticed familiar creative bits that will take larger reign in Amelie. We loved the charming romance, with “blind as a mole” Julie trying not to wear her glasses for their first date, and botching everything. We loved the boomerang knife that turns the plot, and Louison’s ingenuity for fixing the mattress springs, and using suspenders to help paint the ceiling, and ultimately combating the butcher and denizens by filling his bathroom with water.

Yes, really. It’s a must-see.

City of Lost Children

Of the films on this list, City of Lost Children should be considered the “younger brother.” It’s the story of a childlike strongman, One, who is on a quest to find his younger brother abducted by scientists trying to steal his dreams.

Wait, what?

Yeah, so, on an oil derrick surrounded by mines, Uncle Irvin, a brain in a fish tank, instructs a series of clones to strap in children to a dream stealing machine in order to soothe a soulless doctor.

They get the children from a congregation of religious Cyclopses paid off by evil conjoined twins who also use orphans to rob houses. And let’s not forget the other carnival freak flea trainer who psychotropic flea stings and music grinder box makes his victims kill.

While City of Lost Children gets off-the-scale marks for originality, our FANs felt that Jeunet didn’t establish enough empathy for us to really sign on for this wild ride through dystopian melodrama/oddball comedy/thriller.

While the film possibly mocks capitalism and religion as exploiters of child innocence, its themes involve finding family and belonging, something that might have been an easier sell if there were any sane people in the film besides Miette, the little girl who shows One around.

As I said, this Jeunet’s younger child, and if forced to choose, it would be the first I’d kick off the island.

Amelie

The Must-See, feel-good movie of 2001, nominated for 5 Oscars in 2002, the cracked creme-Brulee on many people’s favorite movie list, Amelie is Jeunet’s most famous movie.

It’s the quirky comedy of a 23-year old waitress who was convinced by her “cold-fish” father that her heart isn’t strong enough for emotional relationships. Longing to embrace her humanity, she chooses to be a “do-gooder,” developing stratagems for improving other people’s lives.

Many of my FANs (Film Appreciation Nights at Epiphany Space in Hollywood, FYI) had seen Amelie several times, and continued to love the movie’s irresistible charm, the saturated look – a bold greens, the red dress in a red room – Amelie’s clever stratagems, and all those little details of the character’s lives.

From a writer’s perspective, however, Amelie is not a template. It’s an auteur’s labor of love. We couldn’t submit this script anywhere.

Our hero’s need too overcome her fear of intimacy is small, the stakes don’t rise above most high school break-ups, and she doesn’t have a focused journey or a clear goal. As a result, the middle feels episodic, as we bounce from one charming gag and reveal.

Also, it doesn’t quite work as a love story. Love stories are about two people learning to love, laying down their coping mechanisms in order to come together. Amelie and Nino begin on paper as quirky soul mate opposites, where she’s isolated and he’s not isolated enough (the narrator’s exact phrase is Nino had “too many” playmates as we watch them stick young Nino in a trash can on top of his school desk).

However, Nino doesn’t have a coping mechanism. He’s doesn’t have an issue with people. He’s active, sociable, responsible, and playful. Consequently, he doesn’t have a character arc. He doesn’t give up anything to get the girl.

About the ending: we watch it as Amelie overcoming her false belief and daring to risk. That’s powerful and beautifully positive.

However, if we look a tad deeper, she never really repents of playing God with other people’s lives. Everything falls together as it should (the trickster’s “no harm no foul” rule).

And the actual love story? She pulls this rube Nino through the door and has her way with him. Does it seem like he had a choice in the matter? No.

Did they do the hard work of working through their quirks to grow into love in a way that doesn’t feel obsessive or stalkerish? No.

Was her arc much more than psychological? Nope.

SCREENWRITING SIDEBAR: there are three ways a protagonist can overcome the central conflict of a story: tactical, psychological, and moral.

For example, a guy can’t get through a door. He overcomes by:

- Tactical: he goes through the window

- Psychological: he overcomes his fear of entering, and opens the door.

- Moral: by growing into a better human being, he’s capable of opening the door and winning the love of girl on the other side.

The moral is best. Amelie doesn’t achieve a moral change to get what she wants.

All that to say, despite its flaws, all’s well that ends well, and we still adore Amelie. Writers, steal away ideas for all those character bits (the traveling gnome story line was real, taken from a Long Island family by their neighbors), but remember that not every trickster wins. Amelie and Jean-Pierre Jeunet are professionals.

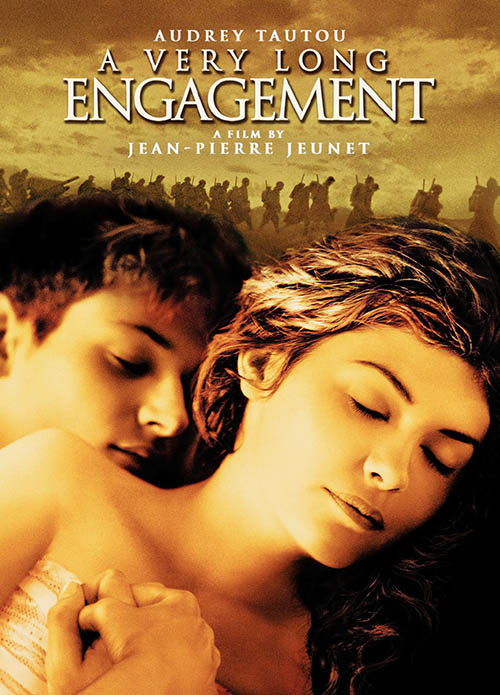

A Very Long Engagement

I have recommended this final Jeunet film to many, and I tell them all that it’s a war movie, because, um, it’s a war movie. It’s WWI, trench warfare, a tale of five guys sentenced to death for “self-mutilation,” wounding their hands in the desperate hope of going home.

I have to mention the war stuff first because the violence may startle those hearing my real reason for recommending it: that it’s one of the richest, most passionate mystery tales of war-time romantic longing you will ever see. That after multiple viewings, you’ll still find more to adore.

Matilda receives the war department letter informing her that her fiance died, but she refuses to believe it. She would KNOW if he were really gone. So she sets off to find him.

She sends letters, posts a request in the newspaper, hires a private investigator, and steals official documents from the ministry of war, taking her down the rabbit hole of those five condemned men at the front lines.

These resourceful men are sent across No Man’s Land toward the German guns. The war department reported five bodies recovered, but the evidence conflicts. Witnesses describe a farmer blown up, but surviving, one with German boots escaping, the Corsican’s lover killing the leaders who sent her man to certain death based on other information, and witnesses describing her fiance Manech, the with one red glove carving “MMM” into a tree before an albatross gets him.

A Very Long Engagement is several love stories in one, and as each mystery unravels, Mathilda gets closer to the truth.

My FANs found it awe-inspiring, the kind of romance Hollywood doesn’t know how to make (challenge accepted, anyone?). They loved the details of each character, the beautiful compositions and set pieces, the symbolism of the hands, wood carving, albatross, the “MMM,” the spiral staircases, etc.

In fact, there’s almost too much. Jeunet begins with descriptions of each condemned man, but because we haven’t been introduced to the main story yet, we have no way of organizing all that information in our heads. We forget much and later have to ask “Wait, which one is he again?”

And then, the ending – beautiful as it is – is also a challenge. Is it a deus-ex-machina? Not exactly, since Matilda provides the requisite information for the investigator to chase down.

Can they rebuild? Jeunet provides the right “call-back” line to suggest it, but one never really knows. One FAN also mentioned the benefit that unlike Gordes, Manech won’t drag his PTSD and wounds into the relationship.

For writers, Gordes represents another potential path for Manech, just as the vengeful Tina (the Corsican lover) represents a different path for Matilda as “war widows.” In other words, Jeunet demonstrates how to explore alternative character arcs through secondary characters.

It’s also great to watch the movie with someone who knows French so we can hear how the subtitles fail to fully convey the beauty behind the end dialog and narration.

There you have it! My list of the best Jean-Pierre Jeunet has to offer. Yes, Micmacs is also available, but I found it too strange. Perhaps I’ll give it a second look, but not before another viewing of A Very Long Engagement.